Over the period of two years, I checked 106,852 email addresses that were contained in public tweets against known lists of compromised credentials. The results showed almost 20% were compromised.

It doesn’t matter how careful you are

It was around 2015 that I first stumbled over the Have I Been Pwned (HIBP) website, a free service that allows you to enter your email address to find out if you’ve been ‘pwned’. For the uninitiated, being pwned in this context means that a website you signed up to had a security breach and now your personal details, very likely login credentials, have been exposed.

Having used the same email address for a long time, despite the fact I was ‘fairly good’ at security, I found my email address was of course, pwned, and my credentials for half a dozen sites were floating around various forums, pastebins and no doubt being sold.

The takeaway from this is, it does not matter how careful you are. By registering for these sites, you are entrusting them with your data and you must accept it is almost certain that at least one of them is going to be hacked or have a data breach.

For instance, we’ve seen LinkedIn suffer a data breach that exposed 164 million email addresses and passwords, Equifax exposed 146.6 million customer’s data, and most recently of course, BA had 380,000 transactions affected by a data breach. They happen, and we have to accept they can happen.

Those who need it the most are at the back of the line

In 2015, I still wasn’t using a password manager and was still guilty of occasionally, using the same password on different sites. Through other precautions and some blind luck, I never actually had one of my accounts hacked. The HIBP website was the thing that gave me the final push to move to a password manager, using strong, unique passwords for every service and 2FA wherever I could.

That year, I did a short talk to a business networking group I was part of about password security and got their permission to run all their email addresses through HIBP prior to the talk. About half of the group had their credentials listed as ‘pwned’ – but more worryingly, when I asked how many people reused passwords, almost everyone’s hand went up. I refined the question to, “How many of you just use a single password for everything?”, about a quarter of the group put their hands up.

Unsurprisingly, nobody had heard of the HIBP website or any of the data breaches their credentials had been involved in.

Proactively alerting users to password breaches

Around this time, it seemed that many companies and websites seemed to be really bad at coming forward and notifying their users when a data breach had occurred. Even in 2016, we saw companies like Uber actively try and conceal data breaches from the public.

I decided to set up an experiment to try and make more of the public aware of the HIBP website and the importance of not reusing passwords. Ideally, I only wanted to contact people who were actively listed as ‘pwned’ on the HIBP website, which mean I needed email address – lots of them.

Fortunately, thousands of people publicly publish their email addresses every day on Twitter and after some playing around with a Python script, I built a method to continuously scan for tweets that contained e-mail addresses. I also needed to add some language logic to try and ascertain whether the tweeted email addresses belonged to the person that made the tweet. That’s a hard thing to do, but I managed to build a basic scoring system that looked for occurrances such as the word “me” just before the e-mail address. With this in place, I had a fairly reliable method to save tweet IDs* that contained email addresses that were likely to belong to the author.

*I chose to save tweet IDs to avoid just build a database containing email addresses.

The HIBP website provides an API which allows you to query an email address to see whether it has been pwned or not. I wrote another small Python script that very slowly worked its way through this list of email addresses and flagged whether they had been pwned or not.

A few tests later and confirming everything was working, I had a built a system that was slowly checking through published email addresses and checking if they were on the HIBP list. I just needed a way to contact people.

Making a Twitter bot

As these users were already on Twitter, it made sense that the most reliable way to get in contact with them, would of course, be Twitter. For this purpose, I made a Twitter bot to send notifications to users if they were flagged as pwned by HIBP.

The trickiest part was trying to build the profile of the Twitter bot and craft the notification tweets in such a way that didn’t make itself look like a scam. In the bio of the bot, I was clear it was an automated service that tried to alert users of compromised credentials and I provided a link to a web page that explained how it worked.

On this page, I provided in layman terms:

- My name and who I was

- A clear statement that I am not asking them for anything at all

- Why my bot had contacted them

- How it got their email address

- How they could verify this information for themselves

- What steps they could take to protect themselves

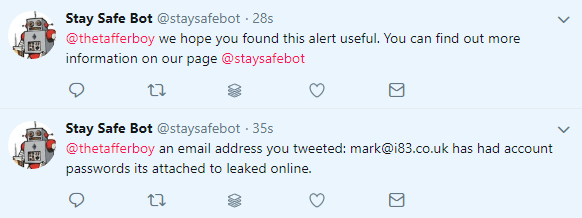

All the tweets that contained pwned email addresses were put into a queue and the Stay Safe Bot would slowly chug through them, sending tweets similar to this:

I did run into a couple of issues with Twitter getting upset with repetitive tweets. To make the bot add a little more value, I also got it to tweet infosec news every few hours, by piping in the RSS feeds from several popular security blogs and news websites. I also wrote several variations of the notification tweets, assigning it to randomly pick one each time.

Once I was happy everything was working as intended, I needed to have the service running 24/7. I decided to use a spare Raspberry Pi, as the power usage was much lower than my PC and I wanted to have everything running locally. With this set up, I popped the Pi into my desk and just left it to do its thing…

The results

I was really surprised by the amount of positive feedback I got from the bot’s notifications. Apart from attracting the odd internet looney, the vast majority of replies seemed to indicate that the message was working, and users were taking the message on board. Checking the Google Analytics of the information page I had linked to, it did appear that a good percentage of those that had been notified, were following up and reading more.

To me, being able to scale this and get people even to think a bit more about password security was a big win.

21,180 of 106,862 emails were compromised (19.8%)

The true number is likely even higher. While I made a fair attempt to automatically cleanse data, we must consider that:

- There were quite a few spam/sockpuppet/porn disposable emails that were checked as part of this process.

- Despite a verification, dead/broken email addresses did creep in.

- There will be more lists with compromised credentials we don’t know about

Considering the above, the ‘real’ percentage of compromised accounts is likely even higher.

It probably shouldn’t have, but this number did kind of shock me. It means that if you pick a random email address that’s been tweeted, there is a 1 in 5 chance that it has been attached to some kind of data breach. As people don’t change email addresses very much but continue to sign up to more websites and have their data spread out further on the web, this number is only going up.

I considered that Troy Hunt, who runs HIBP would have the best data on what percentage of email addresses that runs through his system is compromised. However, even if API queries were isolated, there is likely to be a bias in his data in that the only people that are running email addresses through his system are already aware of HIBP, therefore have some kind of security knowledge.

Although finding that percentage was not the goal of my experiment, I think it’s an interesting and fairly valid figure.

Should you tweet emails that are compromised?

I had this discussion with a couple of people. What were the implications of ‘publicly’ notifying somebody that their credentials are compromised? I thought hard about this and concluded that the ‘pros’ of informing them far outweigh the ‘cons’.

Consider this: If a potential hacker does see the tweet from the bot (which is directly to the user, so this itself is fairly unlikely), the only information they have is that email may be compromised. They don’t know the password or any other information that is not already publicly available. Should they want to act on this information, they will need to get their hands on one of the breach lists, which itself will contain thousands, hundreds of thousands, or in some cases, millions of credentials. I find it highly unlikely that the kind of person that is going to hunt down one of these lists and act illegally on it, will be inspired to do so from a tweet. In my opinion, the far more likely scenario is that the kind of person that is motivated to do this will already have these lists and therefore already be in possession of the information the bot tweeted and a simple search could link the Twitter account and email address in the same way.

These lists are only worth anything while the affected users are still using the same passwords or are using that password for multiple services. The evidence I have from responses seems to show that lots of people were motivated to change their password after receiving a tweet from the bot, which is a good thing. If there are any infosec people out there that think I’ve really overlooked something big, do let me know 🙂

To try and cover any risk I have not thought about, I have deleted all of the tweets from @staysafebot before publishing this article.

Why is the service now stopped?

It was never meant to go on forever or be a proper ‘service’ per se, I just wanted to experiment, see if I could help some people out and/or get any interesting results. HIBP is far more well known now and they’ve got some great integrations with people like 1Password. I also feel that most companies are a lot better at proactively alerting users when they know they’ve had a breach now, rather than trying to sit on it.

Your security

If you haven’t already, go and check your address on HaveIBeenPwned, make sure you use a password manager and follow a few basics to keep your logins secure.

Be safe! (⌐■_■)